One of the great features of the DG Cities team is our mix of public and private sector experience, and the insight this gives us into the realities of implementing technological solutions in housing estates, particularly when it comes to transport. Our Head of Smart Mobility, Kim Smith has been leading transport strategy and delivery for more than 25 years. Here, she draws on this knowledge and the latest analysis to consider different perspectives on a key challenge for EVs: what if I don’t have anywhere to charge one?

We know that transport emissions represent a major hurdle in the move to a zero-carbon future. We know that part of the government’s strategy to address this is to set an end date for the production of diesel and petrol driven vehicles. The uptake of new electric vehicles is growing rapidly, so we can also assume the second-hand market in EVs will also blossom over the next five years or so. We are at the point where EVs are no longer just for early adopters and there is mainstream take-up, but this means that the practicalities for many consumers are coming into sharper focus. One of the key issues: where do I charge it?

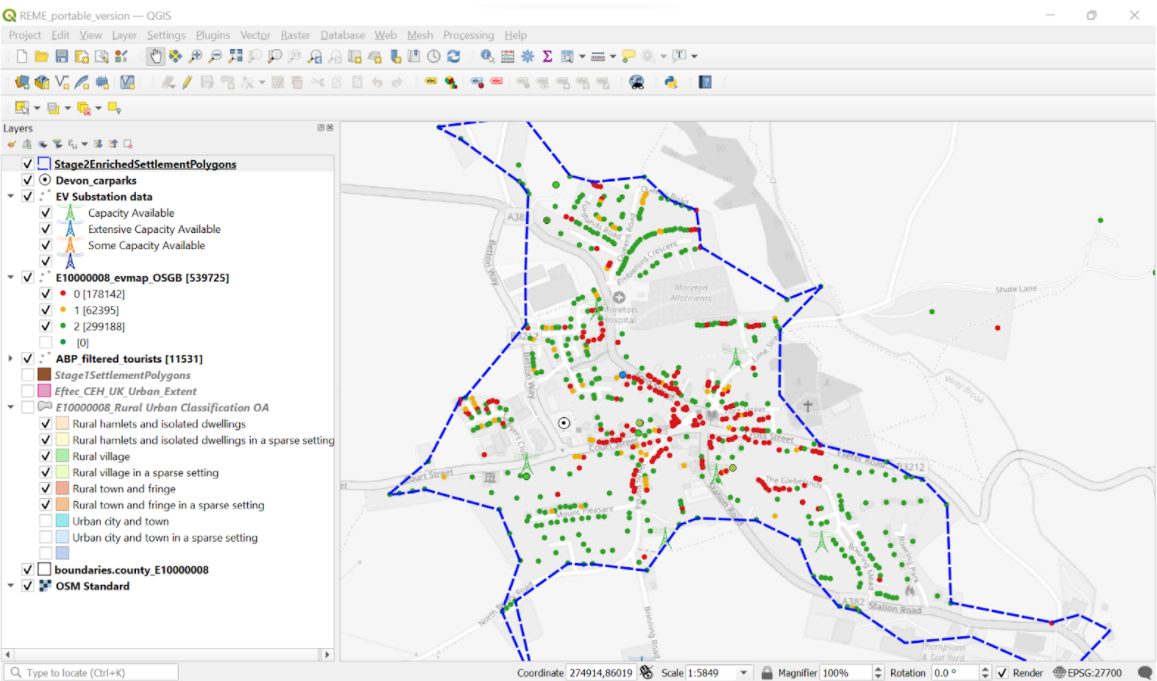

If you have your own dedicated parking space where you can charge your new EV, whether at home or work, then certainly, unless you’re heading off on a trip or covering exceptionally long distances, how and where to charge is relatively straightforward. However, work we have done at DG Cities shows that a high proportion of us don’t have off-street parking. Important to note, our research tells us this isn’t just a city problem – it is equally evident in both urban and rural areas. Figures vary by location, but around a quarter to a third of households don’t have a space at home to charge off-road.

“...do we really need to cover our footways with charge points? Is that not simply an evolution of the car-dominated planning policies of the 60s and 70s?”

Is the solution to fill our streets with EV infrastructure?

There are planning and accessibility issues when it comes to infrastructure on the street: do we really need to cover our footways with charge points for those of us who need to rely on public charging? Is that not simply an evolution of the car-dominated planning policies of the 60s and 70s?

It’s an interesting thought, as we transition away from fossil fuels and the experience of popping to a garage to top up our tank, how our lifestyles and the places we live will adapt to this change. As proponents of the technology, how can we help to ensure that not having a dedicated charger and the associated range anxiety isn’t seen as a deal breaker? One way is to look at the data…

We don’t always drive as far as we think

Battery technology is moving ahead, and vehicle range is increasing, certainly with the more expensive EV options. In theory at least, range anxiety should be decreasing. Additionally, most of us drive far fewer miles than we imagine. Work done recently by our friends at Field Dynamics, looking at data on 140 million records from annual MOT tests over the last four years, shows that, on average, mileage is dropping: pre-Covid average annual mileage has fallen year-on-year since 2019, to 5,506 miles per year for 2021. There are outliers – high and low mileage drivers – however, when broken down further, 57% of vehicles travel less than 100 miles per week, 87% of vehicles travelled less than 200 miles per week.

The anomaly tends to be in the growing market of vans, where higher mileage, combined with (currently) less range, means multiple charges per week are needed. We also need to consider those who are either buying less expensive vehicles with more limited range, or second-hand vehicles whose older battery technology may require more frequent topping up.

What if you live in a flat with no parking?

For residents of flats, especially older blocks, where parking may not have been a consideration for early planners or developers, traditional parking pressure is already a concern. Garage blocks are often used for storage rather than vehicles. The lack of – or in some instances, lack of knowledge about – an accessible, affordable and efficient public charging network is a huge consumer issue and barrier to EV uptake.

As part of our work aiding the transition for council residents, DG Cities is working with colleagues in the Royal Borough of Greenwich to look at charging needs in housing estates. These are often a mixture of high- and low-rise buildings with limited parking. The approach must be holistic, and this project forms part of a wider piece of work looking at Mobility Hubs on estates, and how councils can offer residents a mix of sustainable transport options (watch this space for more news!) However, to ensure tenants and leaseholders in council properties are prepared for the transition to EVs and not left behind, public charge point provision in or close to the estate is being looked at as a priority.

As with all things, the solutions we are seeing are complex, influenced by continually evolving shifts in behaviour and attitudes as much as technology. Consumer confidence comes with education and experience adapting to EVs. This confidence comes from the provision and placement of an appropriate smart public charging infrastructure at a level sufficient to meet demand. But this infrastructure shouldn’t needlessly clutter the environment with more street furniture that prioritises private vehicle owners and harks back to the ‘car is king’ ethos of previous planning regimes. This is the balance that DG Cities is working to strike, in designing and implementing successful strategies that work for everyone that uses our roads and pavements, whether on foot or wheels.

If you are a local authority or land owner looking to identify where to prioritise EV charging infrastructure, watch our film and get in touch to learn how we can help. You can also read insights from our government-commissioned survey into smart EV charging, and a snapshot of some of the data we gathered on the link between a council’s EV strategy and overall take-up.